The first questions I got asked when meeting anyone at the Department were to place me in one of about four types, or castes. It was one of the distinctions I had to keep in mind to understand the State Department, and to function at all, really. Your caste determines how you get into the department, how long you'll stay, how far you can advance in rank, what authority you can exercise, and how much risk you can handle. The four major castes are: political, foreign service, civil service and contractor.

(N.B.: I use the term "caste" here very loosely. It's a usage I've made up, for convenience. Use it at your own risk.)

Political

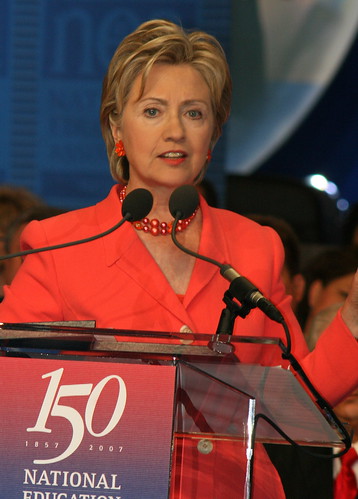

The political appointee caste has the most decision-making authority. Typically, a political appointee, or "political", is appointed into a particular position and stays there for 3-4 years, until replaced by another political. They don't tend to last longer than that, even if the top guy is re-elected, because the appointments are often handed out in exchange for favors during the presidential campaigns; a new set of favors usually means a new set of politicals. Politicals at lower ranks in the bureaucracy may avoid some of this turbulence, just because their jobs are so low-profile. Politicals don't tend to move vertically within an administration, unless a political benefactor orchestrates such a move. So, for example, if Hillary Clinton were to be appointed Secretary of Defense, her Deputy Secretary of State might move with her.

The political appointee caste has the most decision-making authority. Typically, a political appointee, or "political", is appointed into a particular position and stays there for 3-4 years, until replaced by another political. They don't tend to last longer than that, even if the top guy is re-elected, because the appointments are often handed out in exchange for favors during the presidential campaigns; a new set of favors usually means a new set of politicals. Politicals at lower ranks in the bureaucracy may avoid some of this turbulence, just because their jobs are so low-profile. Politicals don't tend to move vertically within an administration, unless a political benefactor orchestrates such a move. So, for example, if Hillary Clinton were to be appointed Secretary of Defense, her Deputy Secretary of State might move with her.Politicals have high decision-making authority, but are often very cautious. Because they are instantly replaceable, they have the ability to make exactly one major wrong decision. U.S. ambassadors are sometimes politicals. The total number of political appointees is usually capped, and the number of those within a department or agency, and even within a bureau, doesn't change very often. Political appointees cannot often be placed in positions previously held by non-political castes.

Non-political castes often defer to political colleagues, even among colleagues of equal rank. This means that the order of political appointments matters for internal politics; if two offices are negotiating through an internal conflict, where one has an appointed political leader and the other is still waiting for a political appointment, the latter office is then at a distinct disadvantage. That deference declines rapidly as a political's term in office comes to a close. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State (not to be confused with the Deputy Secretary of State) is typically the lowest rank of political appointee.

Foreign Service

The foreign service caste can advance the farthest, as they often occupy the highest in ranks in the Department, sometimes outranking some politicals. Foreign Service Officers, or FSOs, enter via an exam, and are promoted in competition with each other. They last in a particular position for 2-3 years, at which time they all play musical chairs to find their next position. The metaphor is apt, since there are fewer and fewer positions at higher ranks, and, like the military, the FSOs exist in an "up-or-out" situation. "Ambassador" is the name of a particular FSO rank; some FSO ambassadors occupy about 2 out of 3 ambassadorships in U.S. missions; the rest are political ambassadorship appointments.

The foreign service caste can advance the farthest, as they often occupy the highest in ranks in the Department, sometimes outranking some politicals. Foreign Service Officers, or FSOs, enter via an exam, and are promoted in competition with each other. They last in a particular position for 2-3 years, at which time they all play musical chairs to find their next position. The metaphor is apt, since there are fewer and fewer positions at higher ranks, and, like the military, the FSOs exist in an "up-or-out" situation. "Ambassador" is the name of a particular FSO rank; some FSO ambassadors occupy about 2 out of 3 ambassadorships in U.S. missions; the rest are political ambassadorship appointments.As stagnation is not an option, the stereotypical FSO is always thinking about the next position, and looking for concrete accomplishments to aid in that transition. This tends to limit her risk-tolerance. High-risk/high-return projects, and those with time horizons beyond her current position, may work against her. Even if she is successful at initiating a particular project, the credit for that success may go to the next FSO in the job, one of her future competitors.

To the extent that FSOs develop specialties, they do so by choosing to advance within "cones": Political, Economic, Management, Consular, and Public Diplomacy. There's no human rights cone

FSOs have decision-making authorities commensurate with their ranks, which often places them across-the-table from their political and civil-service equivalents. FSOs receive no significant deference from equivalents of other castes. Similar to politicals, the negotiating power of FSOs declines as their term in a particular office approaches.

Civil Service

The civil service caste typically occupies policy-making and -executing positions equivalent to FSOs, as well as clerical and support positions. The advancement prospects are relatively low for civil service officers, or CSOs, but their average tenure is long and their job security is quite high. CSOs enter the Department through many means, including via direct hiring, internship, and fellowship programs. Some positions are opened to general competition (and so are advertised on usajobs.gov) and others have pre-selection criteria. The Department has selection and placement arrangements with several organizations, so policy-making CSOs are often Presidential Management Interns, Science Policy Fellows, and the like. The long tenure of CSOs means low turn-over, so open CSO positions are often hard to find. Because of preference quirks in the federal hiring process, these positions may be even harder to fill, even with a surplus of qualified candidates. Though a CSO's position and authority is usually lower than most politicals and FSOs, they have the ability to survive beyond members of other castes, and to have long-lasting impact in the Department. CSOs have the ability–and, perhaps, the privilege–to think long-term, and to take on high-risk/high-return projects. However, as many CSOs become frustrated by being overruled by risk-averse superiors and other castes, they are often reluctant to enthusiastically endorse new ideas.

The civil service caste typically occupies policy-making and -executing positions equivalent to FSOs, as well as clerical and support positions. The advancement prospects are relatively low for civil service officers, or CSOs, but their average tenure is long and their job security is quite high. CSOs enter the Department through many means, including via direct hiring, internship, and fellowship programs. Some positions are opened to general competition (and so are advertised on usajobs.gov) and others have pre-selection criteria. The Department has selection and placement arrangements with several organizations, so policy-making CSOs are often Presidential Management Interns, Science Policy Fellows, and the like. The long tenure of CSOs means low turn-over, so open CSO positions are often hard to find. Because of preference quirks in the federal hiring process, these positions may be even harder to fill, even with a surplus of qualified candidates. Though a CSO's position and authority is usually lower than most politicals and FSOs, they have the ability to survive beyond members of other castes, and to have long-lasting impact in the Department. CSOs have the ability–and, perhaps, the privilege–to think long-term, and to take on high-risk/high-return projects. However, as many CSOs become frustrated by being overruled by risk-averse superiors and other castes, they are often reluctant to enthusiastically endorse new ideas.Contractor

The contractor caste is a peculiar one, and could be the fastest-growing within the Department, though I don't have numbers to back that up. Private companies, often dubbed "government contractors" bid or are selected to perform contracted services for the Department. These services could include security details (the guys in the uniforms with the guns), custodial, maintenance, and construction work, and surge staff for administrative and clerical functions. The individuals from these companies that fill these positions are also, confusingly, called "contractors". Contractors are usually bound by their affiliation to their private company, and can be moved from position to position by that company. This type of movement is rare when the contractor performs satisfactorily, but my impression is that many personnel in the Department could conceivably make trouble for a contractor. Contractors have the option, technically, of operating "to rule", by performing exactly those duties outlined in the originating contract, and no more. However, the pressure to perform satisfactorily can lead to contractors working much harder than this, pushing the limits of wage and hour regulations respected by FSOs and CSOs. Contractors typically don't advance in rank directly, but may leverage the experience they gain in the Department into, for example, open CSO positions. Contractors have authority commensurate with the rank of the position that they fill at the time, and give and receive no special deference to equivalent CSOs or FSOs. Because they bring outside experience to the Department, contractors are in a prime position to promote innovative ideas. However, because their job security is particularly poor, they are unlikely to take risks that put them at odds with their non-contractor superiors and colleagues.

So What?

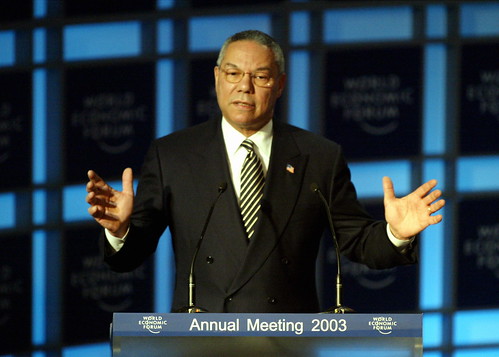

I've emphasized the risk-aversion characteristics of each of these castes for a reason. The last couple of administrations (Powell, Rice, Clinton) have emphasized innovation in diplomacy, through Rice's Transformational Diplomacy for example. Yet many folks in the Department see real contradictions between this push for new ideas and ways of doing business and the structural incentives that individual officers face in pursuing their careers. These conflicts are especially important for outsiders trying to introduce new and important ideas into the foreign policy discussions.

Whew! That's all I have for now on the four major castes in the Department. I hope my knowledgeable friends will correct any mistakes I've made. Of course, I've left out many exceptions, detailees and the like. I also haven't talked about service awards, specifics on hirings and promotions, and myriad other factors that shape and flesh out the castes.

Now, these castes are only part of the picture. Next up in this series will be a rough description of the "tribes" that the Department is divided into: the bureaus and offices. There, we'll focus in on my former bureau, DRL.

[Thanks to Dave for the correction on the FSO cones.]

I don't think I've ever read such a thorough and insightful account of the internal functioning of a branch of government. Thank you!

ReplyDeleteTo me, activists are just lobbyists minus the contextual knowledge and training to be effective. I aim to level the playing field.

ReplyDeleteThat is, you're quite welcome!